Identifying why your baby or toddler is miserable, screaming, unable to sleep, refluxy, colicky, vomiting, prone to rashes etc. is often a daunting task that bears with it a heavy burden of responsibility. It can feel like a frustrating, maddening, and isolating process. You are your child’s best advocate. You are the one spending the nights pacing them through the house so that you don’t feel so horrifyingly impotent and because it seems to marginally comfort them. You are the one weeping because they are clearly so unhappy. You are the one that sees them day in and day out (and often through the night). You are the one with a niggling fear that something is wrong, even if they are your first and only, because they are nothing like the healthy, happy, peacefully sleeping babies you see with other mothers.

There can be a number of medical reasons for the circumstances above and a food allergy or intolerance is one of those (it may also be coupled with another condition such as Gastric Reflux Disease [GERDS] and be a compounding factor for the other condition). Many allergens can pass across in breast milk and even minute traces can be enough to trigger a reaction. For some, the allergy or intolerance may not be apparent until they begin eating solids, or until they’re a toddler, or until they’re almost starting school. I still have vivid memories of sitting in the car as a three or four year old wishing desperately that I could trade bodies with someone to see if they also had a sore stomach all the time; it was so constant and such a naturalized part of my young world that I never told my parents. It wasn’t until a major vomiting incident at a birthday party, triggered by a small ice-cream, that an investigative process started that identified I was intolerant to dairy.

Terms like allergy and intolerance can be bandied around interchangeably in the media, and sometimes by medical professionals, but they have quite different meanings. There are also two different types of food allergies, immediate and delayed, with the former getting more press.

Food Allergy: Immediate: IgE mediated

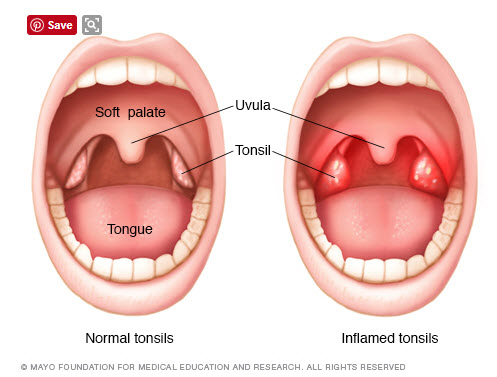

A food allergy is an inappropriate immune response to a particular food protein. An immediate type allergy happens very quickly after the food is eaten (or sometimes after minute traces of the food touch the skin or membranes). Reactions are caused by a particular part of the immune system causing the body to release histamine and other chemicals, leading to hives, swelling, and, in rare cases, anaphylaxis (a severe, life-threatening reaction). A skin prick or blood-specific IgE testing can be useful for diagnosis.

Oral Allergy Syndrome

A sub-set of this is Oral Allergy Sydrome which usually develops later in childhood or in adulthood. It happens after a person develops an allergy to a pollen. As well as getting seasonal hay fever, their immune system starts identifying foods that contain proteins with a similar structure to the pollen. The immune system then mistakenly identifies this food as being pollen when it is consumed and causes a mild allergic reaction in the mouth (such as itching or swelling). This can happen even with food that has previously been regularly eaten without issue. So for example, an allergy to birch tree pollen can cause a reaction when eating apple, peach, plum, cherry, potato, carrot, hazelnut, pumpkin seed and aubergine. A ragweed pollen allergy can cause a reaction to melon and banana; mugwort pollen can cause a reaction to celery and tomato; grass-pollen can cause a reaction to tomato, melon, and peach.

The process of cooking often destroys the pollen-like protein so someone may react to raw apple but have no reaction, or milder symptoms, when eating apple pie.

Food Allergy: Delayed: non-IgE mediated

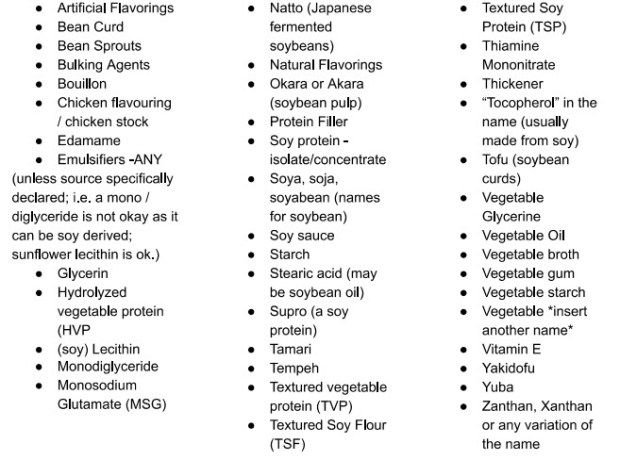

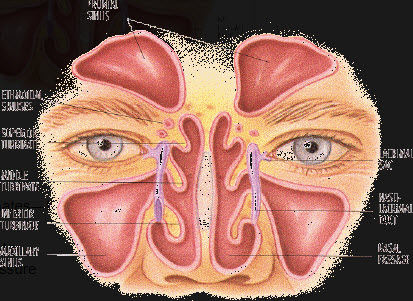

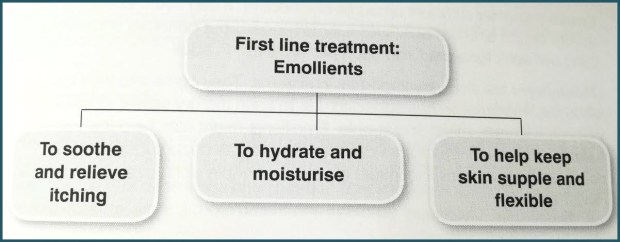

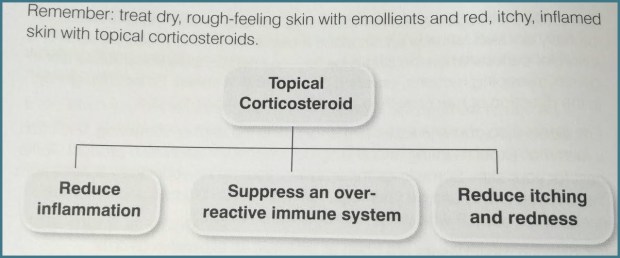

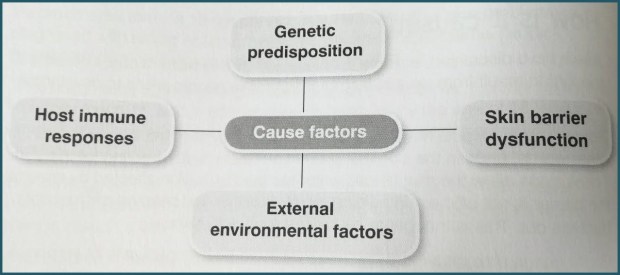

The reaction can occur hours (or sometimes days) after the food is eaten, making them very difficult to diagnose. The reaction is caused by a different part of the immune system to IgE mediated reactions; one of the biggest problems is diagnosis as allergy tests are unhelpful for delayed allergy. In truth, delayed allergy is a spectrum of disease, in terms of severity and where the problems show themselves such as in the gut or skin. The most common causes are cow’s milk and soya, and less so wheat and egg. Typical symptoms may include persistent non-responsive eczema, rash, refluc, colic, diarrhoea, poor weight gain, difficulty feeding, and, less commonly, constipation. Breathing symptoms are rarer and do not occur in isolation, i.e. they may have noisy breathing or a wheezy cough in conjunction with reflux.

Diagnosing often involves detailed daily diaries (covering everything from food, sleep, bowel motions, and mood), food inclusion-exclusion challenges, and working through skin prick and/or blood-specific IgE testing. This should be done under the qualified care of a dietician and peadiatrician. It can be a long, difficult journey but it is important to keep detailed, accurate notes and to persevere.

Food intolerance

“More common than a food allergy, food intolerance is a reaction to food that does not involve the immune system. Although symptoms can mimic an allergy, the causes are different and on-set of symptoms is often slower and longer lasting. Symptoms of food intolerance can include almost anything but most commonly fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhoea and vomiting, bloating (often as part of irritable bowel syndrome) are described.”

Atopic disease

You may hear doctors talk about a family as having a family history of being atopic. “This refers to a group of illnesses, including eczema, hay fever, food allergy, and asthma that are characterised by the presence of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies.”

Atopic illness in a parent(s) makes it more likely that children will also present with these – although they may be to something different. For instance, parents might have asthma, hayfever, and an oral food allergy but their children may have eczema and an allergies or intolerances to different foods than their parents.

Resources

It is important to seek professional medical advice if an allergy is suspected.

There is of course a wide range of information on the web (some more reliable than others). The source that I have drawn on for this post, often quoting directly, is my favourite of the six allergy books that I’ve read in the past two months and the most relevant to my family: The Allergy-Free Baby & Toddler Book by Charlotte Muquit & Dr Adam Fox. I also found it the most approachable in terms of language and found it comforting that it included anecdotes from a number of other families.

My other recommendation is that if you have access to a free public library system then make use of it. Just like finding the right pair of shoes, look at a range of books until you find the one most relatable to your circumstances. If you find one that you really like, and would want to re-read, then buy just that one book. I definitely found it helpful having an understanding of what tests and diagnostic process to expect and I actually took my copy of Charlotte Muquit’s book into some appointments with me.